by Ron Parlato

Programs of “Behavior Change Communications” have been common in the developing world for over 40 years, addressing contraception, oral rehydration, AIDS prevention, malaria control, sanitation, and nutrition. By far, the most difficult and intractable was dietary change – getting people to eat a better and more balanced diet.

Because of poverty, families eat the basics – rice and dal in India, rice and beans in Central America, or their cultural equivalents in other parts of the world. Meat and dairy products are available and known, but out of the reach of poor families. Vegetables are out of the question because they are expensive and provide none of the essential calories and proteins linked to economic productivity and survival, let alone psychological satisfaction. Not only does a protein- and calorie-rich diet provide the nutrients needed to perform hard work, they leave the eater satisfied, with a full stomach. No matter how much one preaches about the importance of green, leafy vegetables, there are always few takers.

People on the margins cannot afford to take risks and, therefore, the wisdom of spending every available cent on calories and proteins – especially for the men in the family who provide income and some semblance of economic stability – is unassailable.

People on the margins cannot afford to take risks and, therefore, the wisdom of spending every available cent on calories and proteins – especially for the men in the family who provide income and some semblance of economic stability – is unassailable.

As soon as families rise out of poverty, they need no education or information to improve their diet. They imitate the middle class and begin to introduce meat, dairy products, vegetables, and fruits into their diets.

About five years after the overthrow of Ceausescu in Romania, behavior change specialists, noting the high levels of smoking, alcohol consumption, and bad nutrition, offered to help design various “lifestyle change” campaigns.

When they suggested that dietary reform might be the logical place to start, the Minister of Health replied that this was the wrong time and place. Romanians had, for so long, suffered food shortages and unvaried, unpalatable products, that eating an excessively rich diet was normal, logical, and in fact very understandable. Good nutrition was definitely not a simple matter.

this was the wrong time and place. Romanians had, for so long, suffered food shortages and unvaried, unpalatable products, that eating an excessively rich diet was normal, logical, and in fact very understandable. Good nutrition was definitely not a simple matter.

Good nutrition in America is no simple matter, either. True, America’s problems have more to do with overeating than under-eating, but the behavioral factors – economics, information, energy output, etc. – are the same. Yet, while the factors affecting nutrition may be similar in all countries, the enabling environment for dietary change is quite different; and, in the case of the United States, particularly complex. For example, suggesting that consumers reduce fat consumption from meat by eating smaller portions, leaner cuts, or moving to fish as an alternative, conflicts with the interests of the Cattlemen’s Beef Association. Reducing fat consumption, by decreasing the amount of dairy products, runs afoul of the National Cheese Institute, the National Dairy Foundation, and the Milk Industry Foundation.

Reducing fat and salt consumption by eating fewer processed and junk foods and saturated fat French fries runs into the buzz saw of various lobby groups. The familiar argument over whether ketchup is a vegetable – an argument which arose out of interest groups trying to improve school nutrition, is an illustrative example of how the diet in America is determined largely by food interest groups.

Reducing fat and salt consumption by eating fewer processed and junk foods and saturated fat French fries runs into the buzz saw of various lobby groups. The familiar argument over whether ketchup is a vegetable – an argument which arose out of interest groups trying to improve school nutrition, is an illustrative example of how the diet in America is determined largely by food interest groups.

The government is complicit in this phenomenon. There are no direct subsidies for vegetables, but potatoes receive generous US dollars. Potato subsidies in Maine alone totaled $535,858 from 1995-2010. Idaho, Washington, North Dakota, Wisconsin, Colorado, Minnesota, California, and Michigan are also recipients. Cheap potatoes allow McDonald’s and other fast-food restaurants to offer huge portions for relatively nothing.

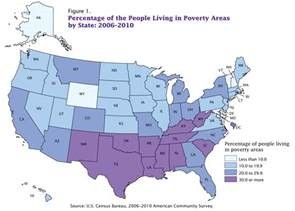

This is just the tip of the iceberg, for obesity is the result of many other factors. The first is poverty. A map of the poorest districts in the United States is perfectly congruent with a map of obesity; and the worst affected are in the Delta region of Mississippi, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Poor families, who used to eat a home-cooked unhealthy diet of cornmeal, fatback, and fried everything, now complement it with the cheap, equally unhealthy foods from the millions of fast food restaurants in the area. At home or take-out, they are clogging their arteries, becoming obese, and dying young.

On the main commercial strip of Columbus, MS, with a population of 25,000 and a per-capita income at $16,700, there are over 25 fast-food restaurants and all the major chains are represented.

People eat fast food because, even though for a family of four the cheapest meals are not cheap, time  constraints for a two-earner household (often with more than two jobs) do not permit eating at home. The poorest families will still cook traditional Southern-style meals laden with fat and calories and with little healthy diversification.

constraints for a two-earner household (often with more than two jobs) do not permit eating at home. The poorest families will still cook traditional Southern-style meals laden with fat and calories and with little healthy diversification.

Fast food has an additional payoff, similar to that for poor Indians, Guatemalans, or Haitians – it is psychologically satisfying. A father who takes his children to McDonald’s and all leave sated after eating the calorie-rich supersized portions can feel responsible and the children never grumble.

Poverty limits exercise. Most people who work at one or sometimes two tedious jobs are tired at the end of the day, and leisure does not include running, cycling, or swimming – even if they had access to the clubs, pools, and cycles of the more well-to-do.

It is difficult enough for wealthy, educated parents to supervise their children, and even harder for poor families who lack the experience, the training, and the will (given their often desperate situations) to exercise the parental guidance and restraint necessary to improve their children’s diets. Moreover, if the parents are overweight because of an improper diet, they are unlikely to demand better of their children.

All the recent flurry of studies on obesity have shown that there are two principal culprits other than poverty – snack foods and sweetened drinks. Hundreds of non-nutritional calories are ingested every week by most adults and children, and the foods that provide them are ubiquitous. Not only are they available in stores and supermarkets, but in vending machines in offices, schools, and public facilities. Airlines, having eliminated proper meals, now give salty snacks like pretzels or chips. Media advertising is relentless.

When asked why they snack, the responses are varied but consistent. Boredom is most often cited. People who work at boring, repetitive jobs with few rest breaks are likely to snack to relieve the monotony. People snack while driving for the same reasons. Others cite associations such as watching TV and snacking.

David Kessler, former Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wondered why people were so addicted to snack foods:

David Kessler, former Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wondered why people were so addicted to snack foods:

“Kessler was on a mission to understand a problem that has vexed him since childhood: why he can’t resist certain foods. His resulting theory, described in his new book, The End of Overeating, is startling. Foods high in fat, salt and sugar alter the brain’s chemistry in ways that compel people to overeat. ‘Much of the scientific research around overeating has been physiology – what’s going on in our body,” he said. ‘The real question is what’s going on in our brain.’” (Washington Post, 2009)

The Dorito is the perfect storm of a bad food – the corn gives it sweetness; it is cooked in fat-giving calories; and it is loaded with salt. Many snack foods provide this tempting and addictive combination. Not only do we reach for snack foods because of psycho-social reasons, once we start in on them, we cannot quit.

There is a genetic predisposition to obesity. This does not mean that a predisposed individual must be fat; but that additional weight is likely if he/she does not take care and watch what they eat. In addition to individual genetic profiles, human beings are programmed to store fat. In caveman days this was important. Hunters who had to run for miles to find, track, and haul game needed sufficient energy; and if there were drought, scarcity of game, or famine, the stored fat kept them alive.

Women, in particular, put on weight to assure that if they became pregnant during lean times, they would be  able to have the resources to bring the baby to term and to breastfeed it. We are no longer under those severe constraints; but not only have we stopped caveman exertion, we have stopped most exertion. Our sedentary lives are perfect complements to the fat genes which are there for survival.

able to have the resources to bring the baby to term and to breastfeed it. We are no longer under those severe constraints; but not only have we stopped caveman exertion, we have stopped most exertion. Our sedentary lives are perfect complements to the fat genes which are there for survival.

Recent studies have shown that truly sedentary activities – i.e. sitting – have a peculiarly odd effect:

“Studies suggest that sitting results in rapid and dramatic changes in skeletal muscle. For example, in rat models, it has been shown that just one day of complete rest results in dramatic reductions in muscle triglyceride uptake, as well as reductions in HDL cholesterol (the good cholesterol). And in healthy human subjects, just five days of bed rest has been shown to result in increased plasma triglycerides and LDL cholesterol, as well as increased insulin resistance – all very bad things. And these weren’t small changes – triglyceride levels increased by 35%, and insulin resistance by 50%!” (Plos Blogs, Obesity Panacea)

It is notoriously difficult to lose weight once it is put on, largely because of the same genetic programming that enabled us to survive the Stone Age. When we severely restrict our diet, our bodies rebel and, noting the decrease in calories, slow down the metabolism, thus burning fewer calories and making weight loss even more difficult. There has also been considerable research done on “set points,” although much of the theory is still being debated.

According to the “set-point” theory, there is a control system built into every person dictating how much fat he or she should carry – a kind of thermostat for body fat. Some individuals have a high setting, others have a low one. According to this theory, body-fat percentage and body weight are matters of internal controls that are set differently in different people (MIT Medical)

According to the “set-point” theory, there is a control system built into every person dictating how much fat he or she should carry – a kind of thermostat for body fat. Some individuals have a high setting, others have a low one. According to this theory, body-fat percentage and body weight are matters of internal controls that are set differently in different people (MIT Medical)

Since it is impossible to determine one’s own set-point, it is impossible to know exactly what your ideal weight would be.

Furthermore, the set-point theory was originally developed in 1982 by Bennett and Gurin to explain why repeated dieting is unsuccessful in producing long-term change in body weight or shape. Going on a weight-loss diet is an attempt to overpower the set point, and the set point is a seemingly tireless opponent to the dieter.

It is easy to see, therefore, why it is difficult for people to maintain a normal weight and even more difficult to lose it. The psycho-social, economic, and political factors affecting weight are so complex, that policymakers don’t know where to begin. Poverty-reduction, for example, is not only a goal for nutritionists, but for the country-at-large; and it has itself been resistant to change.

The political polarity in today’s Congress prevents aggressive action. Republicans refuse more government intervention on principle, citing an aversion to the “Mommy State,” where individual responsibility is superseded by government intervention. Democrats refuse to admit that, in the end, food choices are individual choices.

Technology, usually the best and brightest American solution to problems, has failed on the question of obesity. There is no magic bullet – no pill to take to reduce appetite or to melt away fat. No diet has succeeded longer than a few months, and few people, apparently, are willing to exert the self-discipline and will necessary to carefully monitor “calories in/calories out.”

The attempts to improve nutrition in institutional settings have been overly simplistic and academic, and despite even the most innovative programs to make school meals more attractive and “relevant,” plate-waste is still significant. Just as it takes thought, planning, ingredients, and execution to make a good vegetarian dish, so it takes serious consideration to come up with cost-effective, tasty, nutritious, and especially appealing meals for children.

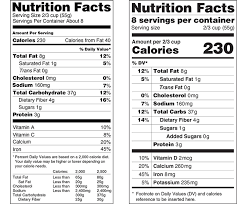

Simple information about good nutrition or the consequences of obesity is not enough – even if public finances and political compromise permit honest media spots. Decades of preaching about “The Four Basic Food Groups” has resulted in little. The explanatory charts on the sides of food packaging – “The Food Pyramid” and now “The Food Plate” – are largely ignored and hard to decipher. Food labeling, especially, has been of little use. No matter what, even if you look at these charts, you still have to do some nimble calculations to determine what you should eat.

Portion sizes, for example, are deliberately adjusted by the food industry to promote their product and to give the impression of consumer advocacy, while only advocating sales. They are quite within their rights, and the consumer needs to be far savvier. In other words, if the portion size is small, then it will account for a lesser percentage of caloric needs. The consumer, not used to mathematical calculations, is taken in. The portion size of hot dogs, for example, is one; but who eats less than two? Or one cookie? Or five nuts?

Portion sizes, for example, are deliberately adjusted by the food industry to promote their product and to give the impression of consumer advocacy, while only advocating sales. They are quite within their rights, and the consumer needs to be far savvier. In other words, if the portion size is small, then it will account for a lesser percentage of caloric needs. The consumer, not used to mathematical calculations, is taken in. The portion size of hot dogs, for example, is one; but who eats less than two? Or one cookie? Or five nuts?

Worse yet is the fact that nutrition labels indicate value by weight or volume; so, few can figure out what 1 oz. of potato chips or pretzels or Doritos is. The standard practical measurement is handfuls – a handful of potato or tortilla chips; so it is quite easy for the hungry consumer to assume that “one portion” is a handful, not a few chips.

While the percentages of MDR (Minimum Daily Requirements) indicated on food product labels are, in principle, useful, they are meant only as a general indicators. The MDR actually varies by sex, age, pregnancy, occupation, and level of activity. A 75-year-old man who is moderately active (not sedentary) requires no more than 1,700 calories to maintain his weight; but an active teenage boy of 17 needs 3,200; a pregnant woman 2500.

It is very easy for an active forty-year-old man to overestimate his caloric needs. He feels like a 17-year-old boy, but his basal metabolism is quite different.

What about calories (or other nutrients) over time? Many people choose to overeat on one day and under-eat on the next. but the tendency is to grossly overeat on the first day and to eat more or less normally on the next. It’s worse if an eater prefers to eyeball his intake on a weekly basis.

And then there is psychology. No matter what the labeling or the professional advice, one measly cookie simply is not enough. An extra shot of vodka after a particularly hard day is warranted and can be worked off at the gym the next day – which it rarely is.

Labeling is all well and good for the individual consumer who is having portions out of a bag, box, or can; but what about the diner at the dinner table. How many calories in an extra portion of au gratin potatoes, made with butter, cream, and cheese? Probably a lot, but how many could there really be in one more helping?

Exercise standards or MDR are equally given to subjective interpretation. “One-mile brisk walk” may be defined as a 20-minute mile, but most people shuffle along at a far slower pace and overestimate distance. Twenty minutes on the treadmill will burn off “x” calories for the serious athlete, but very few for the desultory majority paying more attention to CNN than pace.

So, if few people can make logical sense out of the labeling guidelines and have no idea about the simple mathematics of calorie output, no wonder people put on weight. “Facts” are only partial solutions to persistent problems. Food consumption, even more than sex, is part-and-parcel of a complex psychological, emotional, economic, and social group of factors.

So, if few people can make logical sense out of the labeling guidelines and have no idea about the simple mathematics of calorie output, no wonder people put on weight. “Facts” are only partial solutions to persistent problems. Food consumption, even more than sex, is part-and-parcel of a complex psychological, emotional, economic, and social group of factors.

Dietary guidelines have been a political panacea – satisfying for the bureaucrats who have supervised them, the nutritionists who have concocted them, and the food companies that have influenced them – but, otherwise, only incidental.

This is only the beginning. If misunderstanding or ignoring food labeling and exercise guidelines is common, then imagine when the “powers that be” – the advertising and marketing industries – get into gear. They have always been one step ahead of the social advocates. Food producers are no different from the canny Wall Street investors who created Enron, shady double credit swaps, and bundling of valueless mortgages. They work within public restrictions and legislation, but always find a way to get around them, to entice the consumer, and make money.

If that weren’t enough, behavior change, especially when it comes to food, has always been an impossibly difficult enterprise.

The anti-smoking campaign is a good reminder of how hard it is to change behavior. The Surgeon General’s first warning about smoking and health was issued in 1964, so it has been nearly 60 years of efforts to reduce the nation’s smoking habits. Little happened in the Sixties and Seventies, and only in the Eighties were informational and regulatory interventions begun. Despite the significant decline in smoking, the latest CDC statistics show that nearly 20 percent of adult Americans over the age of 18 smoke, to which must be added an unfortunately high number of those under 18.

Decline in smoking had to do with a number of factors. Cigarette purchase is sensitive to the price per pack – the higher the price, the lower the demand. Local legislation has outlawed smoking in most public places, and the lack of availability of smoking areas has contributed to the decline.

Public information, while not loud and highly visible, has been persistent and has drummed the message about smoking and health into most people’s minds. Successful lawsuits against “Big Tobacco” have put notable pressure on tobacco companies to act more responsibly in terms of sale and advertising. Slowly but surely, social norms have changed, and after 60 years it is most definitely not cool to smoke.

Obesity is no different. There is a particular and indissoluble complicity between food producers and marketers and consumers. Consumers want to overeat salty, fatty foods; we cannot resist them, whether because of some genetic wiring or habit, and producers are more than happy to provide them.

Food with friends and family is never lean, spare, and trimmed down. No one at a good Italian Easter dinner ever had steamed asparagus, skinless, boiled chicken, and a lean, fat-free, egg white dessert. No barbecue was without hot dogs, ribeyes, full-fat burgers, mayo-rich potato salad, and all the sweets you can fit in.

The only lean Americans are those who have demanding physical jobs, but even the formerly most arduous  tasks are being replaced or supplemented by machines. Given our love of food, our genetic predisposition for the most caloric foods, our psycho-social needs to eat, drink, and be merry, and the lack of any meaningful, demanding, and unremitting physical work, it is no surprise that we are fat and getting fatter.

tasks are being replaced or supplemented by machines. Given our love of food, our genetic predisposition for the most caloric foods, our psycho-social needs to eat, drink, and be merry, and the lack of any meaningful, demanding, and unremitting physical work, it is no surprise that we are fat and getting fatter.

If it weren’t for the culture of the gym and the occasional light, fat-free, California-inspired vegan meal, we would be even more obese. Despite the best-intentioned efforts, we simply get fatter and fatter and fatter.